Who would have believed that

one of Indias least industrialised states today, West Bengal, was the ignition of the late 18th century

Industrial Revolution in Great Britain Nobody talks about how Bengal fired up

this turning point in the West.

From early 17th century, India had a superior

cotton manufacturing industry with dye technology, mechanical devices and

elaborate division of labour among specialised craftspeople. Indian cotton was

so popular among all classes of British women that English silk and wool

weavers felt threatened and rioted. So, by 1725, Britain banned Indian

textiles. But the demand for Indian fabrics continued. This stimulated the

mechanisation of Britains textile industry.

Heres how Bengal fits in. The East India

Company defeated undivided Bengals Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah in the Battle of

Plassey in June 1757, as the Nawabs commander-in-chief, Mir Jafar, betrayed

him. This spurred British domination over India. American historian Brooke

Adams has recorded that the Bengal plunder from the Nawabs treasury was so

excessive that it fuelled Britains Industrial Revolution from 1760 and changed

the worlds lifestyle forever.

(from Shombit Sengupta | Shombit Sengupta | Updated: Feb 8 2010, 01:18am hrs)

The conquerors remitted an estimated 1 billion

to Britain. Robert Clive, who led troops against the Nawab, collected 2.5

million for the East India Company and 2,34,000 for himself. His colleague

William Watts grabbed 1,14,000. To put these figures in perspective, an annual

income of 800 was considered sufficient for luxurious living by British

nobleman of those days.

So, says history, the plunder of Bengal post

the Battle of Plassey sparked the Industrial Revolution, which rapidly

auto-mechanised the British textile industry. The inventions between 1764 and

1785 were the spinning jenny by Hargreaves, the water frame by Arkwight, the

mule by Crompton and the powerloom by Cartwright. John Kays had invented the

flying shuttle and coal began to replace wood in smelting, while in 1768 Watt

matured the steam engine.

The spoils from Bengal boosted Britains

economy, but its fallout was de-industrialisation for India. Once England

established industrial capital, it needed markets for selling its products. It

was again Bengal, the first Indian region the British colonised, that was

forced to absorb these goods so England could sustain its Industrial

Revolution. The drain of wealth into Britain destroyed Indias industries, and

impoverishment led to a string of famines. Historian RC Dutt writes, The people

of Bengal had been used to tyranny, but had never lived under an oppression so

far reaching in its effects, extending to every village market and every

manufacturers loom. They ... had never suffered from a system which touched

their trades, their occupations, their lives so closely. The springs of their

industry were stopped; the sources of their wealth dried up. This domineering

British control pushed India hundreds of years behind in economic development.

Those struggling times made our independence

movement look like momentary politics. The call to abandon British manufactured

products, make handloom cloth or get salt from the sea without

industrialisation once again instigated de-industrialisation. Can this be

considered a vision for India or was it just a political shock factor of that

time India today is growing with industrialisation fuelled by foreign

investment from the West. This is changing the countrys economic perspective

for the better. This development is totally opposite to both Indias

de-industrialisation post-1760 and the independence movements methods before

1947.

Not only did the British plunder Bengal in

1757, they created two blunders we still continue to suffer from. First, their

divide-and-rule policy created fissions between Hindus and Muslims in Bengal,

which persist in pockets throughout India today. Secondly, they divided Bengal

into East Pakistan and West Bengal, aside, of course, from creating West

Pakistan too. From 1947, up to 1970, five million people were displaced from

East Bengal. West Bengal is yet to recover from displacement, which continues

till today.

My family fell victim to this political chaos

and had to abandon land holdings and prosperity in East Pakistan. My father,

his widowed mother and 10 siblings came to squat on a piece of land with other

refugees 30 km from Kolkata. Economists say West Bengal ranks third among

states in the number of small retail shops--4.5 million. An estimated 20

million are directly dependent on these small shops. I can vouch for this.

Every time I return to my erstwhile refugee colony, my childhood friends have

expanded a section of their house to set up a small store as they have no other

job opportunity there.

The most frightening part of my refugee colony

childhood was the arrival of the land tax man. Hed go around tom-tomming a

drum, alerting and threatening people to pay land tax on time, or else face

forfeiture of their houses. Our thatched roof, bamboo wall, mud floor house was

small, but at least it was better than the tents the other refugees lived in.

My grandmother Nalini Bala would console me in this nightmare. I recently heard

from my father that the West Bengal government subsequently regularised the

squatters colony and gave free land rights to refugees where their houses

stood. My pleasure in owning this miniscule piece of land is more than having a

farmhouse in California. It must have been the same for landless farmers who

were given land for free. But nobody had taught them the value of

industrialisation, so these landowners cannot understand why suddenly their

land is required for industrial development. People have not been educated on

the need for a balance between agriculture and industry. Without having their

buy-in, its difficult to have industrialisation, so West Bengals livelihood

continues to be small retail stores.

After economic liberalisation in 1991, while

India flourished, Bengal languished. With no industry, locals fight each other

for power and money. The central subject today is who will come to power, not

how to industrialise the state or educate the masses for industrialisation.

As Bengal still reels under the ghost of the

1757 British plunder, only an evangeIist, a thinker and implementer can preach

to the masses the value of bringing a balance between agriculture and industry

to change the states economy beyond any political manifestation.

Shombit Sengupta is an international creative business strategy consultant to top managements. Reach him at www.shininguniverse.com

***

Author: Dr. Jayakumar Srinivasan

Press Release: https://www.esamskriti.com/e/History/Indian-History/Famines-During-British-Rule-1.aspx

- More than 50 million died in famines during British rule, yet many school text books do not mention about them, or say thousands died. Read all about the famines.

To read the same article in Tamil please click on PDF.

Our team was asked by a State Government SCERT Textbook Board to review 6 to 8 standard Social Sciences textbook. We made many recommendations for change of content. The State adopted about half of those suggestions. Let us look at one example.

In the context of the Zamindari system, take a look at the following extract from the 8th standard textbook 1

It is true that the British policies ruined our agricultural system. But let us draw our attention to the sentence “There were great famines which killed thousands of people”.

A famine is a situation where there is an extreme scarcity of food, especially grains. Many of us many not have had a first hand-experience of a famine because the last famine was in 1943. However, much research has been done on the study of famines in India, especially during the colonial period.

In an important book Late Victorian Holocausts 2, summarized by Fred Magdoff 3, Mike Davis mentions that there were 17 famines in the 2,000 years before British rule. In comparison, in the 120 years of British rule, there were 31 serious famines. Davis argues that the seeds of underdevelopment in what later became known as the Third World were sown in this era of High Imperialism, as the price for capitalist modernization was paid in the currency of millions of peasants’ lives. This fact should impel us to understand the British role in creating intense famines in India.

Here is a list of some major famines during British rule in India. 4

| Year | Name | Region | Deaths | Comment |

| 1769–70 | Great Bengal Famine | Bihar, Northern and Central Bengal | 10 Million | About one third of the then population of Bengal |

| 1783–84 | Chalisa famine | Delhi,UP, Punjab,Rajasthan, Kashmir | 11 Million | Severe famine. Large areas were depopulated. |

| 1791–92 | Doji bara famineorSkull famine | Hyderabad,Central India,Deccan,Gujarat, Southern Rajasthan | 11 Million | One of the most severe famines known. People died in such numbers that they could not be cremated or buried. |

| 1860–61 | Upper Doab | Rajasthan | 2 Million | |

| 1865-67 | Orissa famine | Bihar, Orissa, Parts of Southern India | 1 Million | The British Secretary of State for India, Lord Salisbury, did nothing for two months, by which time a million people had died |

| 1868–70 | Rajputana famine | Rajasthan | 1.5 Million | |

| 1876–78 | Great Madras Famine | Mysore and Hyderabad States (Madras Presidency) | 6-10 Mil | |

| 1896–97 | Indian famine | Rajasthan, parts of Central India and Hyderabad | 5 Million | |

| 1943–44 | Bengal famine | Bengal | 3.6 Million | 1.5 from starvation; 2.1 from epidemics. |

In an 1883 Volume on Rural Bengal 5, W. Hunter gives a vivid and disturbing picture of the 1770 Bengal Famine, “All through the stifling summer of 1770 the people went on dying. The husbandmen sold their cattle; they sold their implements of agriculture; they devoured their seed-grain; they sold their sons and daughters, till … no buyer of children could be found; they ate the leaves of trees and the grass of the field; and in June, 1770, the Resident at the Durbar affirmed that the living were feeding on the dead.

Day and night a torrent of famished and disease-stricken wretches poured into the great cities. …pestilence had broken out. … we find small-pox at Moorshedabad, … The streets were blocked up with … heaps of the dying and dead. … even the dogs and jackals, the public scavengers of the East, became unable to accomplish their revolting work, and the multitude of mangled and festering corpses at length threatened the existence of the citizens.

Starving and shelter less crowds crawled despairingly from one deserted village to another in a vain search for food, or a resting-place in which to hide themselves from the rain. The epidemics incident to the season were thus spread over the whole country; … Millions of famished wretches died in the struggle to live … their last gaze being probably fixed on the densely-covered fields that would ripen only a little too late for them…”

About a quarter to a third of the population of Bengal starved to death in about a ten-month period. In 1865–66, severe drought struck Odisha and was met by British official inaction.

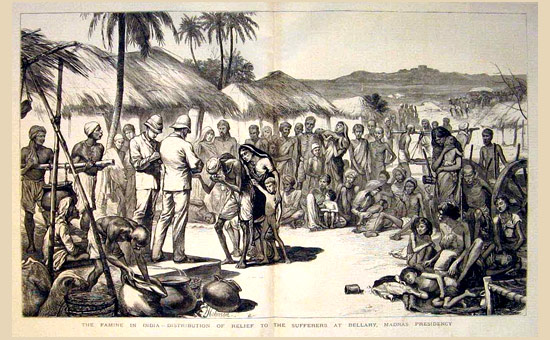

Victims pictured in 1877 Reference 4.

Victims pictured in 1877 Reference 4.

Great Famine 1876 to 78.

An important work to understand the role of British during the period 1939-45 (World War II), is Madhusree Mukerjee’s book “Churchill’s Secret War” 6 where she shows that the 20th Century’s greatest hero is also its greatest villain.

When asked to release more grain to India, Churchill said “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.” When the Delhi Government sent a telegram to him painting a picture of the horrible devastation and the number of people who had died, his only response was, “Then why hasn’t (Mahatma) Gandhi died yet?”

How to imagine the scale of loss?

The Gaja cyclone of Tamil Nadu in November 2018, which devastated the livelihoods of 500,000 families by leveling coconut, cashew and mango farms killed about 40 people. The 2004 Tsunami killed 230,000 across 14 countries.

The number of Indians who died in famines in Colonial India is 50 million. The scale of loss is incomparable.

What can India do now?

Indian school textbooks should bring out British brutality unambiguously, as these were facts of our history. In the absence of critique of the colonial period, students can come away with the false notion that colonization was the best thing that happened to India.

After our team sent this critique to the State, the Editorial Board replaced one word “thousands” by the word ‘millions” 1. While this is welcome, the text makes it appear that the British rule was benevolent to India. That view needs to be refuted and completely restated that the British were disinterested in the welfare of India!

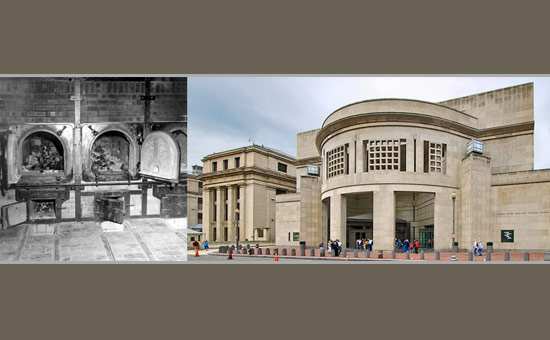

We can also learn from the West. For example, to memorialize the Jewish Holocaust (where close to 6 Million Jews were deliberately killed in Europe during 1941-45), the US has a museum – called the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. In addition, almost every child going to school in this world likely learns about the Holocaust.

The infamous Gas Chambers of the Nazi Holocaust Ref 8n Holocaust Museum USA Ref 9.

The infamous Gas Chambers of the Nazi Holocaust Ref 8n Holocaust Museum USA Ref 9.

India should establish monuments in West Bengal and other places to memorialize this genocide that killed as many people as the World War I (40 Million), and World War II (60 Million).

What were factors contributing to an increased incidence and severity of famines during the British rule of India? We will review this in a future article.

References

1. Social Studies, Class VIII, Hyderabad: SCERT, Telangana, 2018.

2. M. Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso Books, 2017.

3. F. Magdoff, “Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. By Mike Davis 2001. Verso, London and New York,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, vol. 20, pp. 190-192, 2007.

4. “Timelines of Major Famines in India during British Rule.” (Online).

5. W. W. Hunter, “Annals Of Rural Bengal,” vol. 1, 1883.

6. M. Mukerjee, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II, India Penguin, 2018.

7.”Bengal famine of 1943″. To read Bengal famine and Responsibility for Holocaust

8. G. Will, “A showcase of the vilest and noblest manifestations of humanity,” 26 April 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment